Genetic Analysis of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Reveals Polygenicity but Also Suggests New Directions for Molecular Interrogation

Material below is adapted from the SfN Short Course Genetic Analysis of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Reveals Polygenicity but Also Suggests New Directions for Molecular Interrogation, by Benjamin M. Neale, PhD, and Pamela Sklar, MD, PhD. Short Courses are daylong scientific trainings on emerging neuroscience topics and research techniques held the day before SfN’s annual meeting.

Physicians first noted severe mental illness ran in families nearly a century ago. Since then, scientists have confirmed the heritability of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in numerous studies documenting the incidence of mental illness among twins and other family members. Estimates of the inherited component of risk for these mental disorders range from 60 to 90 percent.

Despite this compelling evidence for genetic underpinnings for both illnesses, genetic linkage analyses have failed to find individual genetic variants that confer high degrees of risk. Instead, many genes appear to be involved.

Genome-wide association studies, which simultaneously consider the contributions of multiple DNA variants to a particular trait, would seem to be a good approach, yet researchers who pursue this approach haven’t pinpointed any definitive genetic causes for schizophrenia, even with huge samples. Instead, they find many variants associated with schizophrenia each contributing only a tiny portion of risk. Collectively, the results confirm that risk for schizophrenia is highly polygenic.

Finding multiple genetic variants associated with schizophrenia suggested genetic risk could be described with a “polygenic risk score,” a weighted sum of the number of low-risk variants carried by any one patient. While several groups created such scores, their predictive values have been too low to be useful in clinical settings.

Interestingly, polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia also predict bipolar disorder, indicating that the two illnesses, considered to be clinically distinct, may share genetic underpinnings. Using another approach known as genome-wide complex trait analysis, scientists found substantial overlap in the genetic basis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, suggesting that the illnesses share biological pathways.

Gene variants that contribute mild risk for schizophrenia often code for proteins involved in neural processes that have previously been identified through pharmacological approaches, particularly dopamine and glutamine signaling. But researchers have identified many illness-associated genetic elements in non-coding regions of the genome that are presumably regulatory in nature. Maps of relationships among regulatory elements and genes — the focus of several consortium projects — will help to sort this out.

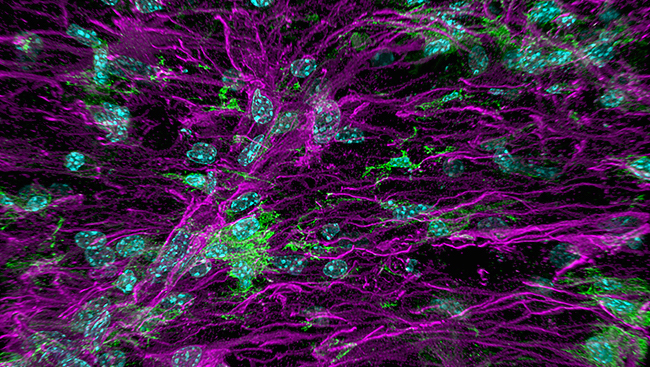

Projects to “annotate” the genome, that is to catalog biochemical modifications of the chromatin that influence how genes and regulatory sequences interact, are beginning to be used to select particular genomic regions for biological follow-up studies. Researchers using this approach have flagged CACNA1C, the gene for a subunit of one type of voltage-gated calcium channel. Whole-exome sequencing efforts implicate genes for voltage-gated calcium channels as well as proteins that modify postsynaptic structures in the development of schizophrenia.

Previously, calcium signaling hadn’t been considered as a mechanism in either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Its role in neural development, particularly in the growth and guidance of axons in developing and differentiating neurons, points to an intriguing line of inquiry for teasing out the origins of both illnesses.