The Story Behind This Former NIH Program Director's Career

This resource was featured in the NeuroJobs Career Center. Visit today to search the world’s largest source of neuroscience opportunities.

No two careers are identical. Yet, all neuroscientists will likely share certain commonalities: the first sparks of scientific curiosity, difficult challenges, resilience to press on, accomplishments large and small, hard-earned wisdom, and support from professional and personal communities.

In this series, Notable Careers: Reflections on Science, Leadership, and Community, five neuroscientists reflect on their life’s work and share their hope for the future of the field.

Here, Michael Oberdorfer, whose last position was program director of NIH’s National Eye Institute (NEI) extramural research program, shares his initial childhood curiosity with science and nature, highlights from his training years, what it was like to attend SfN’s first annual meeting, and more.

What inspired you to become a neuroscientist?

As long as I can remember, even as a little kid, I've been interested in nature. I spent some of my early years in Kensington, MD. Our house backed up against deep woods, and I was always bringing home critters — snakes, frogs, turtles — and it didn’t stop there (it drove my mother crazy).

I became interested in the nervous system when I was in high school. Neuroscience was a somewhat rarefied topic, and it was mainly clinical. I spent a lot of time looking at insects and marveling at how much they could do with a very small nervous system.

I was lucky to end up in a highly collaborative, fairly egalitarian scientific environment at Madison.Then, I read Nerve Cells and Insect Behavior by Kenneth D. Roeder.This fascinating book was essentially about the aerial interactions between moths and bats and how the neural activity in certain species of moths translates into evasive behavior when they realized bats were tracking them. I learned more about these kinds of neural and behavioral interactions from Roeder when I spent a year at Tufts University in the late 1960s.

These topics aligned exactly with my original interests in natural history. I watched bats as a kid and marveled at how they swooped, dove, and caught insects in the air. Now, I had scientific explanations because people studied the neural activity of certain moths and saw how they responded under various circumstances when preyed upon by bats.

What was your neuroscience training like?

For graduate school, I ended up at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, a great place to be. I was a graduate student in zoology and later in the emerging discipline of neuroscience. I had the chance to learn and ask questions, which was encouraged there.

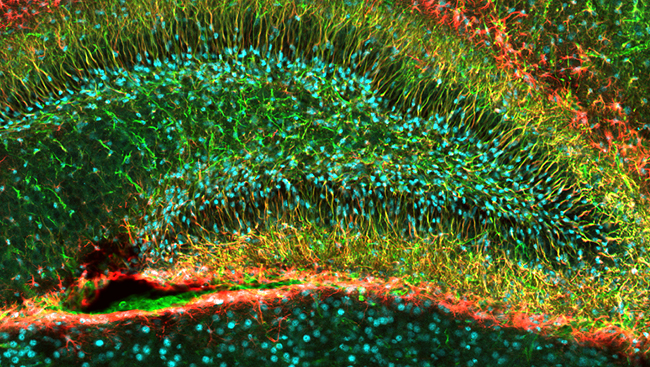

I became interested in vision, which later led to my work at NEI. I stuck with my interest in arthropods. For my thesis, I studied the visual system of jumping spiders, learning a lot about the organization of one part of visual system and also finding many parallels with the visual systems of mammals.

This research interested Ray Guillery — probably one of the greatest modern neuroanatomists who ever lived — and I did a postdoc with him. I began working with mammalian visual systems, a fairly natural segue. From Guillery, I learned about neuroplasticity and visual systems.

I was also influenced by Clinton Woolsey, Jersey Rose, Ruth Bleier, and Wally Welker in their neurophysiology labs. John Kaas and John Alman were there too, and I participated in experiments on the organization of the visual system of a number of different animal models. They were establishing the physiological organization of some aspects of the visual system, and I assisted to some degree. All of these scientists shared their questions and insights with students.

It was a nicely blended integrative approach, which is inherent to neuroscience. And, all of these people were very helpful mentors, and plenty of interesting discussions were part of the deal.

What role did collaboration play throughout your training?

Collaboration certainly made my experience richer. We would test our own ideas with the ideas of others, and invariably a new synthesis would result. I felt like I contributed something, even though I wouldn't call them great breakthroughs.

I was lucky to end up in a highly collaborative, fairly egalitarian scientific environment at Madison. People visited the campus from other universities around the world, and I learned from them all.

Granted, I hadn't done that before, so I had to learn by doing.In my research, I explored different invertebrate models, and I saw parallels with mammalian systems. In zoology, I was under the tutelage of Mac Pisano, who studied the neural nets in hydra. Phillip Ruck, who was a gifted sensory physiologist, was also in the zoology department.

I also frequently learned from other students. For example, when I was a teaching assistant at Madison, I learned from the questions asked by undergraduates. They didn't ask cut and dry questions, but rather oblique ones. I’d sometimes respond, "I don't know," and a discussion would follow.

I learned it’s essential that neuroscientists at all levels be collaborative and open to learning new topics. Scientists should also not be afraid to ask questions. They’re the beginning of a collaborative process because they spark conversation, and they help you learn from other people.

What came next for you after training?

For a little while, I stayed at Madison as a class instructor in the medical school. From there, I went to the University of Texas as a faculty member.

Then, I was asked to go to NSF to start a new program in developmental neurobiology because of my background and interests in the development and plasticity of the nervous system. While I was there, I was asked to join the extramural branch of NEI at NIH to work as a program director, so I decided to do that rather than return to the University of Texas.

What were you focused on at NSF and NEI?

At NSF, I was asked to start a new program area in developmental neurobiology because they were getting an increasing number of applications in that area. I had to pull together a panel of people — similar to an NIH study section — who would evaluate the applications and make funding recommendations based on the discussion of the panel. Granted, I hadn't done that before, so I had to learn by doing.

At NEI, one of the newer NIH institutes at the time and a source of support for my postdoctoral studies at Wisconsin, I focused on funding visual neuroscience. A lot of research was getting underway, so we were trying to support a lot of new and exciting research.

NEI had a lot of similarities with NSF, but it was a more structured environment and a very large place. NIH institutes have a separation of review and program, whereas at NSF, they were integrated under one program officer.

During my tenure there, I also worked in the lab when I sliced out free time. I worked on the auditory system to avoid conflicts with my day job as a program director at NEI. While at NEI, I also directed the Low Vision and Blindness Rehabilitation program. It was a great chance to develop funding in this area, particularly by encouraging neuroscientists and others to see it as a research opportunity.

I also spent time encouraging support for women in neuroscience. There were many young women who were bright and had many great ideas, but so much of neuroscience, like a lot of scientific fields, was dominated by men at that time.

To some degree, I appreciated the struggles these women faced because I grew up with a single parent — my mother. My father died when I was young. I saw what my mom had to put up with, and when I think about how difficult it was for her, she was a real hero. The fact that everybody plays a part was a very important lesson to learn, and I tried to apply it to my work at NEI.

How did being a member and volunteer leader at SfN impact you?

I actually went to SfN’s first meeting, held in Washington, DC, in 1970. I was part of a presentation with three or four other people. We were preceded by a presentation by John C. Eccles. We were worried that everybody would leave the room as soon as Eccles finished his talk, but mostly everyone stayed.

They didn't ask cut and dry questions, but rather oblique ones. I’d sometimes respond, "I don't know," and a discussion would follow.At that 1970 meeting, there was an aura of great excitement that a new discipline was forming. Neuroscience research had previously been presented at other scientific meetings like the American Association of Anatomists, the Physiological Society, and other groups. SfN was intentionally an interdisciplinary blend aimed at advancing an interdisciplinary field.

Throughout the years at SfN’s annual meetings, presentations at poster sessions enabled me to meet, engage, and listen to people. The meeting provides a venue to discuss future work, develop your career, and find collaborations.

For years through SfN, I've also been particularly involved with animal research issues. We have worked to understand people's views against animal research. Scientists in all disciplines, particularly neuroscientists, have to speak with the public about the importance of animal research.

SfN, and societies in general, can make a big difference on policy issues with the input of membership. Right now, all areas of science are under attack. There are windows societies need to take advantage of to generate more interest in science among legislators and the public.

I also still keep in touch with my NEI colleagues through SfN and other professional societies like the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) because they have important roles.

Besides continuing your involvement with SfN, have you remained connected to science in your retirement?

Since retiring, I keep in touch with my NEI colleagues through SfN and other professional societies like ARVO because they have important roles at these meetings.

I still enjoy neuroscience immensely and try to participate. The Neuronline Community enables me to stay connected to other scientists, and I post frequently in the forums, primarily about animal research.

As I still live in the Washington, DC, area, I volunteer at the National Museum of Natural History. It is a great place to interact with people on ideas about science. I work in the public enrichment programs and with insects and arthropods, including tarantulas, taking me back to where I started.

How would you advise scientists, especially individuals just starting out their careers, to build resilience?

Be prepared to reinvent yourself. Don’t get too rigid in your own thinking. Know you will have goals, and many of them will shift because the road in front of you is going to change.

If something doesn't work out, learn from your mistakes. Take a failed experiment. It’s actually narrowing the path to one that will work. Instead of being down, think, "That's one path I don't have to worry about anymore. I can pursue Plan B because it will give me more insight into what’s going on."

For young investigators in particular, when you feel devastated by a bad review by an NIH study section, personal interactions are key. If you feel you aren’t getting the kind of feedback you want, talk to the people whose job it is to help you express your ideas more clearly. The only way you’re going to be successful with funding is to work with others.

At NEI, I drew on my own experiences. Scientists would email me after receiving their summary statements. I would then ask them to call me after they let it fester for a day or two and read it again after they were calmer. I wanted to go over it together and see what we could find out, because at the core of the summary statements is something instructive to build on, or in very rare cases, do something else.

What is your hope for the future of neuroscience?

My hope is that neuroscience continues — the research isn’t done by any means. Every time you've answered one question, other questions just as important emerge.

You never know where the next answers and discoveries are going to come from.

That's why you need to cultivate environments where questions can be pursued by well-trained researchers. Young scientists in particular have so many great ideas because they think off the grid, try new approaches, and take risks.

It’s critical to fund places where this type of research can be done. And it’s important to make these places accessible. I'm appalled by what it costs to attend universities.

It also seems to me we need environments that integrate disciplines, where people can go in different directions and reintegrate and reinvent themselves to advance neuroscience.

Speaker