Inside a Career Built on Perseverance, Curiosity, and Seeking Opportunity

This resource was featured in the NeuroJobs Career Center. Visit today to search the world’s largest source of neuroscience opportunities.

No two careers are identical. Yet, all neuroscientists will likely share certain commonalities: the first sparks of scientific curiosity, difficult challenges, resilience to press on, accomplishments large and small, hard-earned wisdom, and support from professional and personal communities.

No two careers are identical. Yet, all neuroscientists will likely share certain commonalities: the first sparks of scientific curiosity, difficult challenges, resilience to press on, accomplishments large and small, hard-earned wisdom, and support from professional and personal communities.

In this series, Notable Careers: Reflections on Science, Leadership, and Community, five neuroscientists reflect on their life’s work and share their hope for the future of the field.

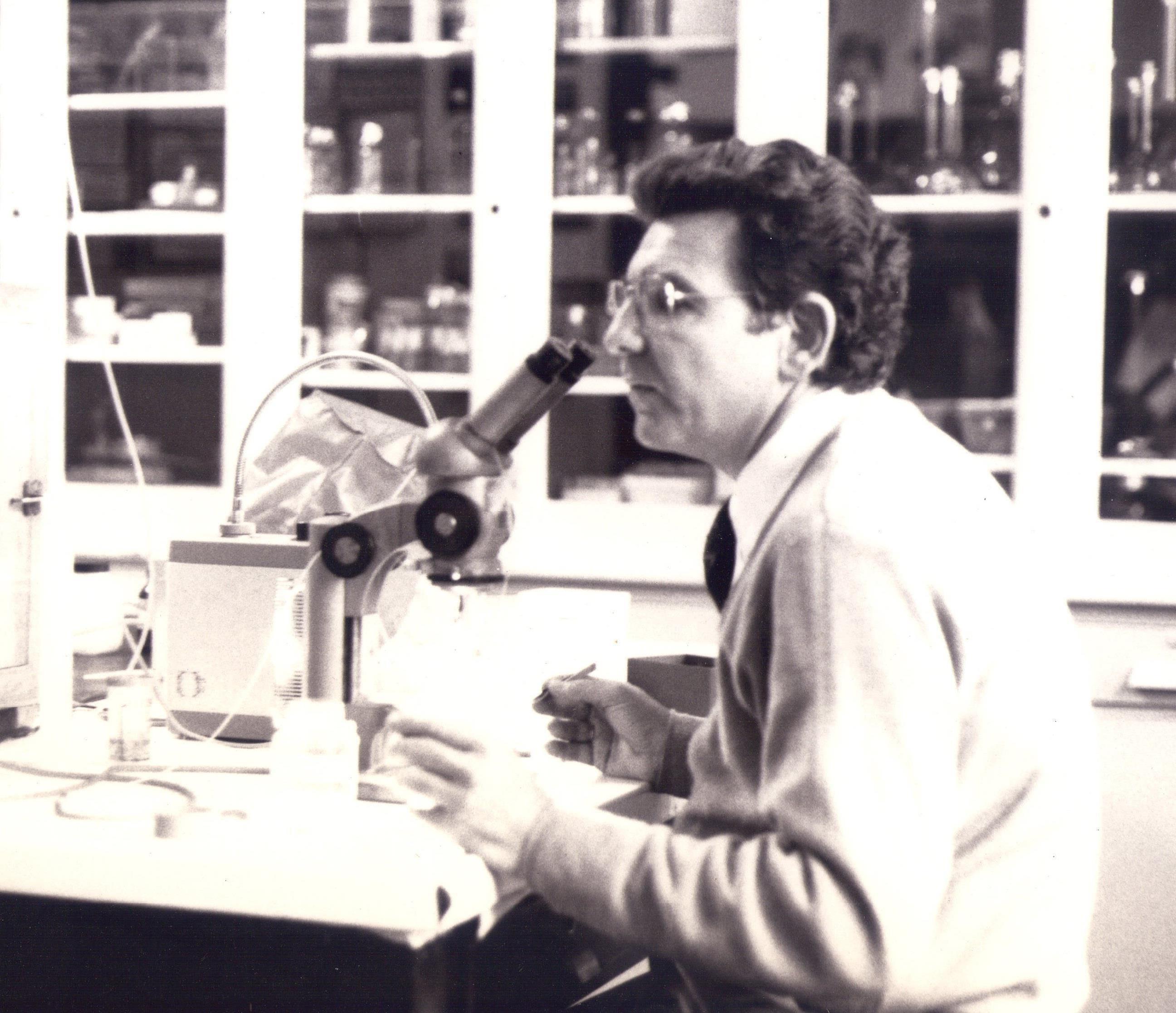

Here, Osvaldo Uchitel, whose last position was senior researcher at the University of Buenos Aires, focuses on what it was like to conduct high quality science and rebuild a community of neuroscientists in Argentina despite a volatile political climate and scarce funding and scientific support.

What inspired you to get involved in neuroscience?

I was born and educated in Argentina. In my first year of college, I went to a lecture given by Edward De Robertis, a neuroscientist who led the team that discovered synaptic vesicles. He showed us an electron microscope picture that captured my attention.

From that moment, I wanted to learn more about cells and how they work. At first, I was more interested in research than clinical work. But then I started working on how nerves and muscles interact, bringing me closer to neuroscience and neurology.

Neurology, the clinical part of neuroscience, was poorly developed at that time. It was mainly a tool for diagnosis and putting a name on the disease, but it had nothing to offer to patients. That pushed me to search for the actual cause of the disease, which led me to study diseases like myasthenia gravis, Lambert Eaton Syndrome, and more recently, migraines.

What are some highlights from your career?

In 1973, I presented my data on the first recorded calcium currents in muscle cells at a local meeting in Argentina. I met a well-known Chilean electrophysiologist, and he invited me to take a course there about voltage clamps, which was a sophisticated technique at the time.

So, I went. This was one month before the Chilean coup overthrew the democratic government and ushered in a dictatorship. Our conditions doing science were impacted by current events. We didn’t have enough food while we were working, and I had to build my own bed in my residence. In spite of that, we still did highly sophisticated experiments and would celebrate them by dancing on the beach.

Later, when I was a postdoc, I worked in a lab in the biophysics department, headed by Nobel Prize winner Sir Bernard Katz, at University College London.

I spent five years in London working in an international lab with 14 countries represented, which was so important for my career. It was a huge highlight for me to exchange ideas and learn how people think and approach science from different backgrounds.

Years after I came back to Argentina, I was invited by Andrew Engel from the Mayo Clinic to collaborate on experiments looking at human muscle from biopsies from patients with myasthenia gravis. I had to set up the whole system and equipment to do the physiology in just two weeks. We were running against the clock. But, after two weeks of hard work, we discovered new congenital myasthenic syndromes.

What accomplishments make you most proud?

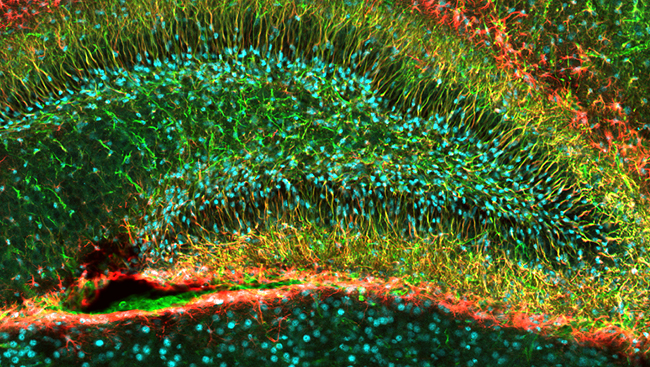

I feel proud of my collaboration and friendship with Ricardo Miledi and Rodolfo Llinas because we made important contributions in the field of synaptic physiology, in particular on the role of acetylcholine receptors and calcium channels.

I'm also proud of my contributions to neuroscience education. When I returned to Argentina, the neuroscience field was devastated. I had to start from scratch trying to teach students, but eventually we built up a community of neuroscientists in Argentina and Latin America.

I became so involved with SfN and the Federation of Latin America Neuroscience Society (FALAN) because, along with advancing science, I thought it was important to develop this scientific community. I feel proud that I pushed the development of neuroscience in Latin America and how I represented Latin America through my participation in SfN.

I feel strongly you have to do the best you can in your environment. My environment was not easy. We didn’t have a lot of resources, but with highly motivated students, we still kept our science at the highest level.

Did you have any significant challenges in your career? How did you overcome them?

My biggest challenge was returning to Argentina and starting a lab from scratch with no resources.

I had to start from scratch trying to teach students, but eventually we built up a community of neuroscientists in Argentina and Latin America.If I had to describe my career in three words, they would be: perseverance, curiosity, opportunity. I knew it would take time and effort to be able to build up a lab in Argentina, but I persevered.

I actually had the opportunity to go to any other country and set my lab up, but returning home was important to me.

I had no funding, so I thought about what could be cheap as a biological preparation. So I used tissues from human biopsies because I didn’t have to pay for them like I would have had to for the other animals, and it turned out to be really great.

I looked for my opportunity. But I also looked for collaboration.

I was in Argentina testing sera from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) patients. I knew Stanley Appel in Houston, TX, from my time in the United States, and he was working on the subject. I called him, and without being shy, said, "I want to and need to collaborate to survive as a scientist." He agreed, and it worked out well.

How would you advise scientists to build resilience in the face of adversity?

Always have an alternative plan. With the project you love, you can run into difficulties. Having an alternate plan to do other work will give you time to improve your main objective when it’s not working properly.

It’s also important to be open to the community around you. When you face difficult times, your friends in the lab and elsewhere can provide valuable support.

How would you describe your mentoring philosophy?

I was open and listened to my students. I wanted them to be independent. So, my lab shifted to have an open atmosphere. If a student came up with an idea, I would let them follow their own, original paths. Of course, I always reminded them how rigorous they needed to be with their experiments.

We didn’t have a lot of resources, but with highly motivated students, we still kept our science at the highest level.I also emphasized that they shouldn’t rely too much on the technicians and others who support the research in the lab. While they are always helpful, the students have to know and control every single step of their experiments and learn to work with their own hands.

Finally, I encouraged my students to go to other labs with different resources and points of view for experience. That's something that we sometimes struggle with in Argentina and other Latin American countries. People do their PhD and postdocs in the same labs, and that's not always good.

What do you think makes a collaboration successful?

You have to be open when you collaborate. Don't be shy about asking for more information to understand what others are doing.

It’s easy to feel intimidated when you collaborate with a strong group. There was one point when I felt that way, so I didn’t speak up to ask questions to understand what they were doing and how I could contribute.

Later on, I learned I was capable of much more than I thought. The best advice I can give is to be sincere in your questions and find your self-confidence.

Why do you think it's important for neuroscientists today to be involved in professional societies, like SfN?

Now that neuroscience incorporates so many disciplines, being involved in a professional society like SfN can put you in contact with people from different facets of the field. This creates a strong community and gives you the opportunity to participate in the development of the field. Students should be curious about what other people do and how they do it. Societies like SfN can facilitate their exploration.

What is your hope for the future of neuroscience?

I strongly believe science will build bridges across cultures for progress and peace.

However, the brain is extremely powerful, which can be dangerous. If you learn how the brain works, you have the capacity to manipulate people. It's risky to leave that knowledge in the hands of only a few people. I hope the future of neuroscience is universal, belonging to the whole world.

*Photos provided by author.

Speaker