Halfway through my second year in a neuroscience graduate program this winter, I encountered a new challenge in the lab. Unlike last year, when I endured the pressure of exams, the monotony of daily classes, and a feeling of not belonging, this year I experienced something else: failure.

It is frequently said that to be a scientist is to fail. That’s easy to say and understand in theory — until you go through it yourself.

My failure came in the form of various experiments and techniques that I’m familiar with not working. In one instance, I had trouble replicating an immunohistochemistry experiment performed by my principal investigator. In another situation, I couldn’t find a behavioral phenotype while manipulating a particular neuronal population. Several of my planned experiments were also delayed due to mis-genotyping of animals. In addition, because I am in a new, small laboratory, I set up and troubleshoot every technique or paradigm that I want to use, which can be tedious.

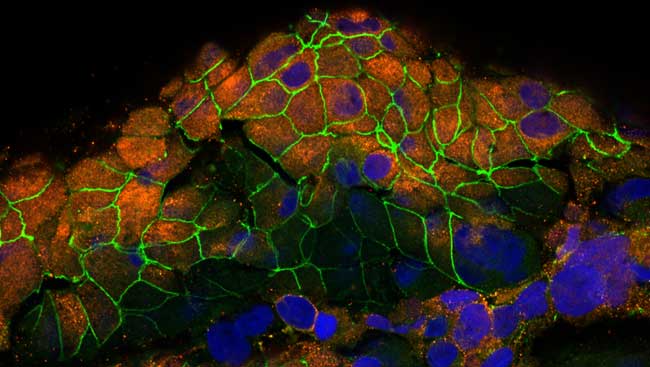

When I heard that graduate school was difficult, I anticipated late nights peering over results to develop a unifying theory that would explain my findings and expected long hours running experiments and juggling priorities. Instead, I’ve found myself spending more time reading about techniques online and performing them myself only for them to not work. I’ve also spent hours on the confocal microscope, only to realize that a small mistake made days ago will yield sub-par images.

During this slump, I drew inspiration from Mindset by Carol Dweck. In the book, Dweck, a psychologist and sociology researcher, describes the two attitudes people have toward their abilities.

Individuals with a fixed mindset believe that their abilities are static. Someone with a fixed mindset might also be described as deterministic: a person has intelligence, or they don’t, they are capable of a specific task, or they aren’t. Individuals with a growth mindset believe that their actions can improve their abilities, meaning that achievement is not a function of fixed traits, but rather an interaction between natural talent and effort.

Dweck notes that individuals with a growth mindset welcome failure because they see it as an opportunity to grow, whereas individuals with a fixed mindset fear failure because they see it as evidence of their limited abilities.

Now, I am trying to view my setbacks with a growth mindset, which is surprisingly challenging. It is easy to write off failures as products of the environment: My mice are anxious, or the new microscope slides are faulty. It’s much harder to seriously evaluate my abilities and accept that I still have a lot of room to improve.

I’m coming to realize that this is graduate school. I am in school to learn, and learning can sometimes be painful and frustrating. I am strengthening my abilities to cope with the realities of academic science and persevere through any challenges. So I keep reminding myself that each difficulty I overcome is building my resilience and will make me a better scientist.

Read Kavya's follow up article Coping With Failure as a Grad Student and Beyond.