Vivian Mushahwar on Challenging Herself in Spinal Cord Injury Research

|

|

|

This resource was featured in the NeuroJobs Career Center. Visit today to search the world’s largest source of neuroscience opportunities.

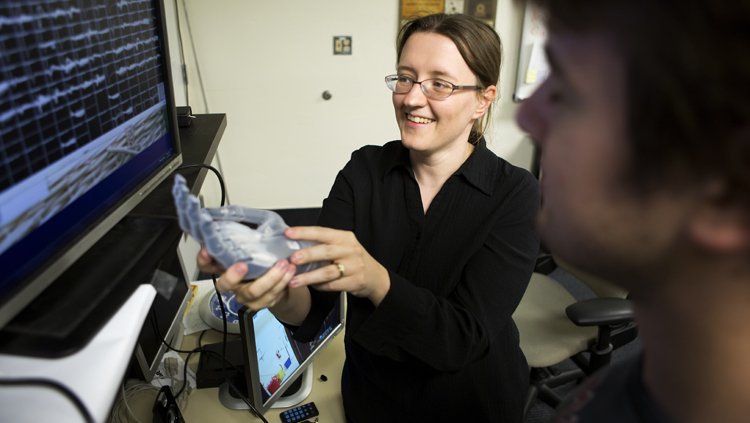

Vivian Mushahwar designs rehabilitation interventions for people with spinal cord injuries. Director of a state-of-the-art center for researchers from engineering, medicine, rehabilitation, computer science, and neuroscience, she’s working to alleviate the effects of spinal cord injury through innovation and entrepreneurship. In this interview she walks through her career path in detail, shares how mentors have guided her, and offers advice for trainees on discovering your passion, choosing a faculty position, and navigating challenges as a woman in science.

This article is part of Neuronline’s interview series “Entrepreneurial Women Combining Neuroscience, Engineering, and Tech,” which highlights the career paths and scientific accomplishments of female leaders and role models who are creatively bridging disciplines to improve lives.

How did you discover your interest in biomedical engineering?

My dream was to make people walk again.I studied electrical engineering in undergrad. I love physics, and I love math, but I felt a bit isolated in terms of the lack of human impact. I felt I really needed to be able to use my science to make a difference in somebody’s life.

So, I started researching how I could use my engineering background for a biomedical approach. I was at the library when I came across the field of bioengineering. The description was “using engineering solutions for medical problems.” It was exactly what I was looking for.

I wanted to interface with the human body — the spinal cord, specifically — and try to restore its function. My dream was to make people walk again. That's basically what I wrote in my personal statement for graduate school, “I’m going to make people walk again.”

What projects have you pursued and why?

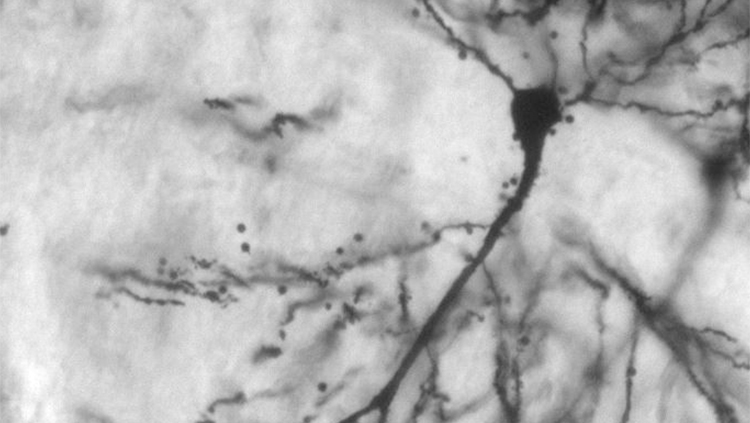

I started off very focused, using intraspinal stimulation as a method to understand the science and the connectivity of the spinal cord.

This expanded my interests to look at other ways to improve mobility. I realized that when people in neuroscience and in the clinical world talk about walking, they focus on the legs, but what about the arms? Why couldn't we use cycling as a way to understand how the arms affect the legs during cyclical movement, and then as an intervention to improve walking?

We found that if people cycle with their arms and legs, they double the improvements in their walking. That’s exciting not only because of the improved outcomes, but from a perspective of cost and the number of people this intervention could help.

Then we started looking at techniques that would allow us to prevent or reduce the rates at which secondary conditions to spinal cord injury develop, using intelligent wearable devices. One is called Smart-e-Pants (Smart Electronic Pants), which prevents the formation of pressure ulcers, and the other is the SOCC, or Smart Ongoing Circulatory Compressions, which prevents deep vein thrombosis.

Walk us through your career path so far.

In grad school at the University of Utah, I focused on learning the neurophysiology and neuroscience components I’d been lacking, working mainly with animals. By the end of it, I felt a bit dissatisfied. Is my goal to make an animal or a human walk?

So I decided to do my first postdoctoral fellowship at Emory University, which let me work with people with spinal cord injury. I wanted to understand their real problems and how I could use a technique called intraspinal microstimulation to help them.

During a conference, I was giving a talk about my graduate work when a professor approached me. He found my work fascinating and said he had a technique to implant electrodes in animals while they were awake. This was exactly what I wanted to do next to get closer to figuring out a human application.

I ended my postdoctoral fellowship early and brought the project to the University of Alberta. We were successful in testing microstimulation to restore walking for the first time in an awake animal. That was a breakthrough.

Of course an implantable system takes a long time to develop for humans, so I stayed in that postdoc for three years before I finally felt ready to apply for faculty positions.

You had offers from five universities and chose to stay at the University of Alberta. What went into that decision?

I decided to stay for two reasons.

First was the interdisciplinarity. I was an electrical engineer as an undergrad, a bioengineer as a graduate student, a relocation specialist during my first postdoc, and a neuroscience and spinal cord specialist in my second postdoc. I saw the value of all these fields coming together, and in the end, it was only the University of Alberta with an environment that allowed for that interdisciplinary interaction. It’s been beautiful.

The second reason I decided to stay was a funding opportunity offered through the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. If you were accepted as a Foundation scholar, they paid your salary and guaranteed 75% of your time was protected for research. That was just so exciting for me. You could apply to renew the salary funding every five years. It was competitive, but I wanted to challenge myself to meet that bar each year and continue to meet it throughout my career.

In the end, I love to work in teams, with different areas of expertise coming together, and I love to be kept on my toes, so the University of Alberta was the right environment.

For any new postdocs looking for faculty positions, you don't need to take your first offer. Look around and find a place that will help you grow and advance.

Who or what has been most helpful to you in navigating your career?

As you're trying to discover your passion and how to pursue it, it's important to talk to experienced people who are willing to take the time to share their experiences.

Mentorship was critical. I've been incredibly fortunate to have had fabulous mentors all throughout my career. There wasn’t a formal mentorship program at the University of Alberta, but I approached people who were receptive and caring, and they eventually became my mentors.

As you're trying to discover your passion and how to pursue it, it's important to talk to experienced people who are willing to take the time to share their experiences and to advise you on a viable path.

My graduate supervisor really opened my horizons. He recognized my interests in restoring walking as well as working with different groups and thought I might manage teams in the future. He encouraged me to take courses in physiology, physical therapy, and business, and I did that as a graduate student, which is not very common.

And that same professor expected all of us to be communicating, presenting our work, and networking with people. I was pushed to be out there talking to people, and to have the courage to do that.

Another part of my graduate training was taking a course that required me to actually write a grant application, not just learn the theory of grant writing. My mentors reviewed my applications and provided comments, which gave me a clear understanding of how to write winning proposals.

What has your experience been like as a woman in a traditionally male-dominated field?

I have two brothers, and my parents treated us exactly the same and expected the same out of the three of us. During undergrad and grad school, even if I was one of the only women, I was used to it and didn’t feel like I was treated any differently.

As an independent investigator, though, I noticed that everyone looked at me. I don't know if it was because I was a woman or young, but either way, it made me not want to be dismissed. So, I figured out ways to make sure I was taken seriously — sitting in front, asking questions — and it worked in that I was able to become well-noticed in the field.

It's not all gorgeous. Sometimes you are treated differently, and you’ve got to figure out the smartest ways to navigate that. It doesn’t make it right, but it always helps if you have higher-ups who know you and who are willing to help you.

I don't know if it was because I was a woman or young, but either way, it made me not want to be dismissed. The culture is changing, though, and I think this is good for both men and women. There’s more interaction, acceptance, and acknowledgement of the skills everyone brings to the table.

I am the director of a research center, and we're still unbalanced with about 70% men and 30% women. We would like to do better, but it's a process. I think it depends on the environment and on the person themselves — how they present themselves and how they're able to stand up to challenges.

What advice do you have for women considering careers in neurotechnology?

One of my mentors, Tessa Gordon was a well-established woman in research. In addition to how to be a successful scientist, she taught me how to be a successful woman in science. The bottom line? Just go for it and never cut yourself short. Push yourself to be the best that you can be.