Rewards and Challenges of a Faculty Career at a Teaching-Focused Institution

This resource was featured in the NeuroJobs Career Center. Visit today to search the world’s largest source of neuroscience opportunities.

Of all of the four-year colleges and universities in the U.S., relatively few are classified by the Carnegie Foundation as R1 (“very high research activity”) or R2 (“high research activity”) schools. While research universities tend to be larger and have more faculty, the small number of them means that most faculty job opportunities are actually at teaching-focused institutions.

While each institution and department is unique, faculty who build their careers at primarily undergraduate institutions (PUIs), experience some common rewards and challenges, many of which I’ve observed first-hand. Here’s what a faculty career at an undergraduate institution can look like.

Rewards of a Faculty Career at a PUI

You can have a larger impact on your department and the institution.

An individual faculty member has more sway at a smaller institution than at a large one. Smaller institutions have fewer programs and resources, but they also have fewer people seeking grant funding and interested in taking on leadership roles.

Teaching-focused institutions need faculty leadership in all the same areas as research institutions do, so you are much more likely to get those leadership opportunities. And at smaller institutions, if you focus on what you feel is important and work hard at it — research, student success programs, curriculum development or revision, etc. — your success will have a noticeable impact in your department and for your institution.

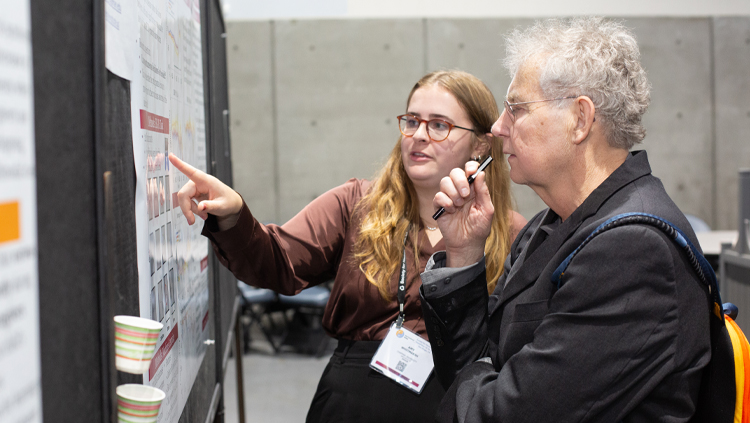

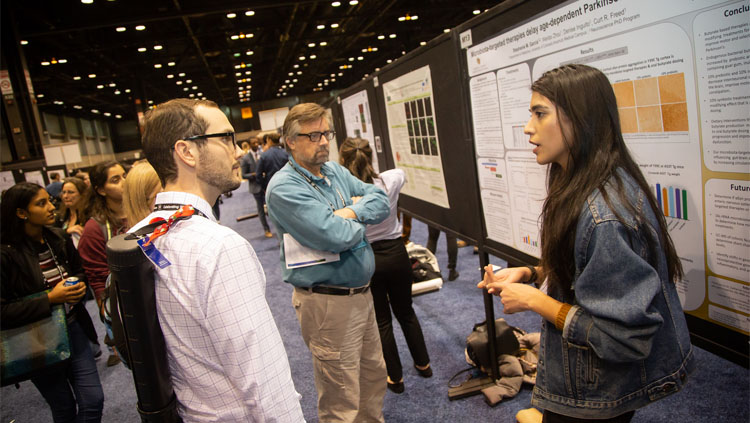

You’ll develop close relationships with students in the classroom and your lab.

At a teaching-focused institution, your main responsibility as a faculty member is to work with students in the classroom. At most institutions, you won’t have teaching assistants, so you’ll be responsible for every element of course delivery. While that is a lot of work, the classes are smaller, so you’ll spend a lot of time interacting directly with students. By the end of the semester, you’ll know your students’ names — and for many of them, details about their lives, challenges, and dreams.

You’ll play a role in helping them to achieve those dreams, and if you are doing research, your workforce mostly will comprise undergraduates. You’ll be the one who trains them, designs their experiments, monitors their progress, and helps them troubleshoot. You’ll become a significant person in their lives for a year or two, and then you’ll get to do it all over again with your next group of students.

You have more control over your work-life balance.

As is the case with any job, in order to keep your faculty position, you must fulfill your responsibilities, which include holding your classes, being present for office hours, and contributing to running your department. At many primarily undergraduate institutions, this is enough. Others may require some level of research involving students. Very few will expect publications beyond one or two, pre-tenure.

With the lower pressure for research success, most faculty have a reasonable work-life balance. In general, they spend eight hours or less on campus each day and don’t come to campus on weekends or holidays, and many even take summers off. Faculty who go beyond that reap rewards for their achievements, but single-minded dedication to work is a choice that they make, not a requirement for success in the job.

You’ll work closely with people who fulfill many different roles at the institution.

Another benefit of teaching-focused institutions is that the academic community tends to be much smaller. Research labs are staffed almost entirely by students, so there are not the armies of research staff who work at research institutions. This means that departments are smaller and can be more collegial, with only one or two support staff with whom you will work almost daily.

You’ll likely work closely with your chairperson and have opportunities to serve on committees or regularly attend meetings with deans or other administrators.

The Challenges of a Faculty Career at a PUI

Institutional support for research will be limited.

You’ll feel this from the beginning, with a small to nonexistent start-up package, followed by limited lab space and lack of access to core facilities and advanced instrumentation. Not only will the teaching load be heavy and release time limited, but a lack of administrative support means your time also gets taken up with administrative tasks such as placing orders and navigating student hiring processes. You may also find that the library has few journals relevant to your research, or that students have limited access to databases such as ScienceDirect or JSTOR. These limitations will not prevent you from doing research, but they will lower your productivity.

The community of researchers will be small and have a limited range of expertise.

With departments small and staffed with many faculty who are not active in research, the pool of expertise you’ll have to draw on at your institution will be limited. Forming relationships and collaborations with researchers at research universities will be crucial for getting access to resources not available on your own campus, so it may be worth seeking to build your career in an area where there are major research universities nearby.

You’ll spend most of your time teaching, whether in the classroom or the lab.

If you don’t enjoy spending time with undergraduates, you should not take a job at a primarily undergraduate institution. Not only will teaching or tasks related to teaching take up most of your day, but your time in the lab will also be spent teaching students. Just when the students get enough research training to be somewhat independent, they will graduate, and you will be teaching a new group.

The community is too small to function as a meritocracy.

With a smaller number of faculty and staff to carry out the functions of the institution, the pool of candidates for opportunities is smaller, too, and it may be difficult to replace those who move into leadership roles. In addition, in a small community, personal relationships are very important. The combination of these factors means that advancement opportunities may not go to the people with the most merit, but rather to people whom decision makers feel are the easiest to work with, or who can be the most easily replaced in their current role.

Careers at teaching-focused institutions may lack some of the prestige of those at research universities, but the rewards are substantial. What we give up in the impact of our research, we gain in the impact we have on students’ lives, and a better work-life balance for ourselves.