How Clinical Training Impacted This Physician’s Choice to Research Pediatric Developmental Disorders

- Featured in:

- Neurobiology of Disease Workshops

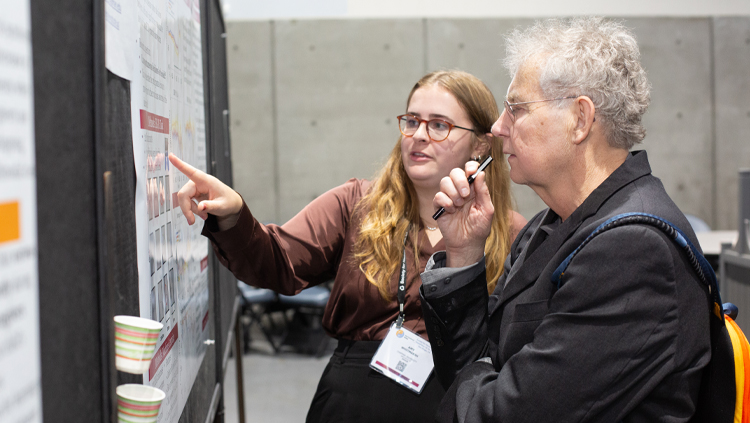

Joseph Gleeson is the director of the Laboratory of Pediatric Brain Diseases at the Rockefeller University and investigator at Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He explains why he dedicated his career to studying and pursuing treatments for developmental brain disorders. As told to, and edited by, SfN staff.

I came in to research pretty late. It was while I was doing my residency in child neurology. I was struck by the number of kids that would come into the hospital with medical complications of an underlying brain disorder. They were hospitalized for pneumonia or feeding problems. There was also a young child who I was taking care of that had fetal exposure to alcohol and was left devastated — unable to speak, unable to communicate — and my heart went out to her. I just wanted to do something to help. If we can change the life of a child, the child has their whole rest of their life to benefit.

As a pediatrician I was left to wonder, “What could have caused all of these problems?” We didn’t really seem to have any answers and no treatments at all. So I went into the lab after I finished my clinical training and started to research developmental disorders of children. This has been my passion.

I’ve always been driven to understand how the brain works, how we think, and how we feel. Even when I was young, this is what I wanted to do. Developmental neurobiology is such a great intersection between how the brain develops, how we think and how we feel, and how the brain is put together to mediate those very human characteristics.

I am really excited that, for the first time now, we have the ability to correctly diagnose kids. We are starting to see some treatments. Still, it is going to take many years from when we know the genetic causes to when we have treatment. We can use cystic fibrosis as an example. It took roughly 30 years and now there are starting to be some new drugs that are coming that will be very effective. Some people might say it took too long and I would agree, but at least something is coming now.

Structural brain disorders are going to take — I am sorry to say — probably even longer because we are dealing with a problem that starts in the womb. How can we think about treating these? We are fortunate that some of the conditions we are seeing now have drugs already targeting those pathways that are deranged. We don’t yet know how plastic the brain is. If we start to treat at birth, how much recovery can we expect? How much degeneration can we hope to prevent? These are the kinds of questions that experiments are building up to answer.

We take clues from the cancer field and from other kinds of fields, like cystic fibrosis, where treatments are a generation ahead of where we are in neuroscience because in neuroscience, we are still learning about how the brain works. We are still learning about how memories are laid down and how the brain cells connect with one another. We need to understand those things before we can really expect to affect potent treatments.

Joseph Gleeson presented at the Neuroscience 2015 Neurobiology of Disease Workshop, Human Brain Malformations: From Genetics to Therapeutics.

Speaker