The following case study is adapted from a Theme J abstract (formerly Theme H) presented at Neuroscience 2015. Theme J abstracts cover topics related to history, teaching, public awareness, and societal impacts in neuroscience, allowing departments and organizations to showcase the work they have done in these areas.

Online courses are increasingly popular, especially for students who need a more flexible schedule due to work or family commitments. However, studies show that online courses have a high attrition rate, and that students who take online courses are less likely to return to school in subsequent semesters and are less likely to earn a degree.

One solution is a hybrid course with online and face-to-face components. Studies of hybrid courses show similar student outcomes to entirely face-to-face courses. I’ve had the same experience when teaching them.

How should I structure a hybrid course?

A flipped classroom approach is one answer. This technique shifts the introduction of topics outside the classroom so that class time can be spent exploring complex ideas in greater detail.

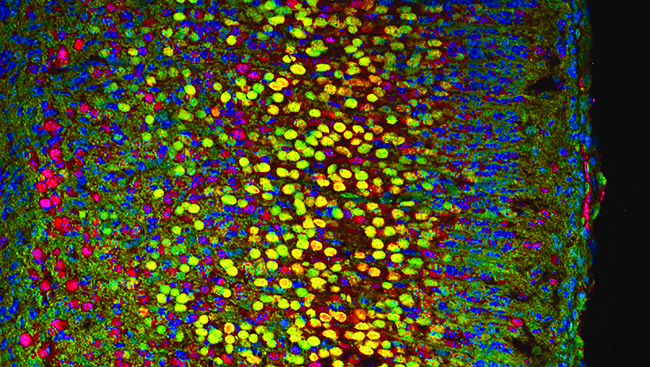

For example, excellent online resources can provide students with a basic working knowledge of action potential generation. After students familiarize themselves with the subject outside of class, they can discuss a more in-depth aspect of the topic, such as the unique structure of voltage-gated sodium channels that facilitates action potential propagation, in class.

Where do I find reliable sources to introduce each topic?

The Public Education Programs initiative, maintained by SfN, links to a wide range of teaching resources. Crafting a good search string that includes the type of resource and educational level you’re looking for can avoid an overwhelming number of results.

Textbook-associated websites allow instructors to assign quizzes that are graded immediately to provide students with automatic feedback. I have used Pearson’s Mastering Series, Sinauer’s Sylvius, and Sapling Learning’s Higher Ed Series.

TED Talks and TED-Ed offer short and engaging videos on many topics. Some of my favorites are How Bacteria “Talk” by Bonnie Bassler, Brain-to-Brain Communication Has Arrived. How We Did It by Miguel Nicolelis, The Cockroach Beatbox by Greg Gage, and The Neurons That Shaped Civilization by Vilayanur Ramachandran.

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute BioInteractive site hosts a collection of resources on various topics. The Holiday lectures on neuroscience, Making Your Mind: Molecules, Motion, and Memory by Eric Kandel and Thomas Jessell and Medicine in the Genomic Era by Christopher Walsh are among my favorites.

iTunesU has many open-access courses and seminars from reputable institutions, such as Stanford’s Hacking Consciousness: Consciousness, Cognition and the Brain by Michael Heinrich and Human Behavioral Biology by Robert Sapolsky.

What teaching strategies should I use for our classroom time?

Case Studies

These are carefully selected stories that personify an important concept. Case-based teaching facilitates the application of concepts to new situations — the prized third level of thinking in Bloom’s taxonomy. In addition, case-based teaching can be blended with constructivism, collaborative learning, or Socratic questioning, methods that play an important role in student learning or “unlearning.”

Make use of the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science’s case study data base sponsored by NSF.

Discussions

I use the following hooks to get students interested and spark discussion:

- Mythbusters: Popular articles from newspapers or websites can be used. I encourage students to bring in topics that we explore together. We may even design experiments to test them.

- Journal articles: We discuss definitions and concepts in the introduction to understand why the authors investigated the topic of the paper and what the results mean.

- Popular books: They are easy to understand and allow students to use their knowledge to more deeply probe topics. Oliver Sacks’ The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Daniel Levitin’s This is Your Brain on Music are great to spark discussion.

Lab Activities

In groups of 2-4, students submit abstracts describing their proposed research, including hypothesis, relevant background, and basic experimental design. These elements are so closely tied together that students must work as a group instead of dividing and conquering. Writing the background and justification for their project also helps them make connections and see how to apply concepts.

How do I set students up for success?

Success of the flipped classroom hinges on students completing the independent assignments before class. I work hard to reinforce this idea on the first day of class, keep outside class assignments manageable and engaging, and provide incentives for completion. I also use quizzes and peer reviews of performance in group activities to hold students accountable.

Arguably, the most important thing I do for student success through the hybrid flipped classroom approach is to empower each student to be responsible for their own learning.