Editor's note: The following post is the second of a pair of essays about interdisciplinary teaching featured on the Neuroethics Blog. Please see its companion piece, Why I Teach With a Neurologist, by Laura Otis.

It is often said that academic fields are becoming increasingly siloed as specializations become more detailed and jargon-filled with each new peer-reviewed paper. The classes co-taught by Professors Otis and Sathian were unique interdisciplinary spaces where students across traditional disciplinary divides wrestled with topics shared by the humanities and sciences: perception, imagination, and art.

Is this kind of interdisciplinary inquiry a necessary counterbalance to the siloing of the disciplines? Or could it even be seen as part of the ethical practice of science? Might having more of such classes improve the science literacy of those in the humanities and keep scientists in touch with the depth of expertise that other fields can contribute? Should we begin to find ways to institutionalize more of this type of work into the higher education system, or provide more movement between the disciplines? Or is interdisciplinarity merely a fad? Readers: what do you think?

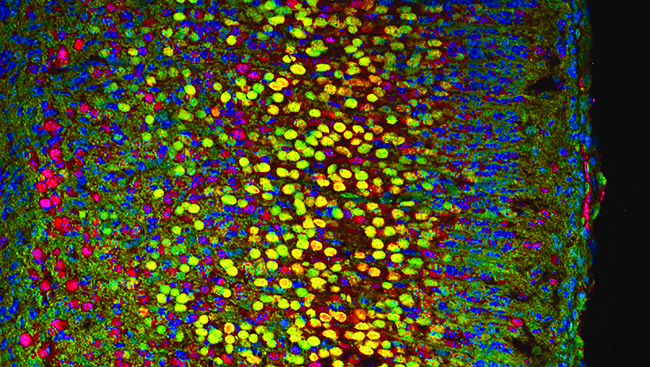

I consider myself very fortunate to work as a clinical neurologist in academia and as a neuroscientist investigating fundamental questions about the brain that may in time have an impact on how we treat people with neurological disorders. My own research over many years has concentrated on studies of perception, but I recently began to study how the brain handles metaphor.

This may seem like quite a jump, but it turns out that sensory and motor regions of the brain are not just involved in the expected sensory and motor functions; they also serve to “ground” metaphors relating to particular sensory or motor processes. For example, when we hear the sentence, “She had a rough day,” the part of our brain that is important for judging roughness by touch actually becomes active. This kind of finding supports the idea that metaphors begin as conceptual abstractions from our experience.

Literature, of course, has an abundance of metaphors, as well as sensory images that are evoked by the words on the page. My background in perception taught me that the experience of imagery depends on activity in many of the same brain areas as are relevant for sensory experience. For example, when one visualizes, the visual cortex, which is necessary for vision, gets engaged.

Thus, one can conceive of literary writers as having mastered the ability to trigger neural processes underlying imagery and metaphor (and other literary devices) in the reader, albeit not necessarily with neuroscientific facts in mind. Of course, I should emphasize that our study of the underlying neural processes is still inchoate.

The Center for Mind, Brain, and Culture (CMBC) at Emory University brings together scholars from a variety of disciplines to examine specific issues from multiple perspectives. One of the ways they do this is a call for interdisciplinary course proposals. With my interests in the neuroscience underlying literary images and metaphors and the expertise of Professor Laura Otis in teaching English in relation to cognitive science, it seemed to us that an ideal course to propose would be one that intertwined literary and neuroscientific readings.

The CMBC agreed to sponsor our course, and I can honestly say that the course we ran in 2012 and its successor in 2014 were the most fun courses I have ever been involved in. We had a good mix of students from various aspects of the humanities and sciences who were keenly interested in the material. The classes had animated discussions from a range of viewpoints.

I went into the first course confident that it would be a good one, especially because Professor Otis, an expert in literature and its pedagogy, also has a background in neuroscience. I thought, however, that we would have to work very hard to eke out a few intersections between the language of storytelling and poetry on the one hand, and that of cognitive neuroscience on the other. Boy, was I wrong!

I was simply blown away by the profusion of connections between disciplines. Professor Otis had a knack for bringing in the right creative works and the right writer-scholars to talk about them. This matched up with the relatively fledgling attempts to tackle how the brain works to enable the glorious acts of literary writing, and the consumption of the products of these acts by readers at large. These pairings really made the courses tick.

Based on my experiences, I highly recommend joint teaching of interdisciplinary courses. It takes some thought and care to select the best topics and generate the appropriate blend of approach and content. Of course, it also takes the right chemistry between the professors and a willingness of students to be open and participatory. When all these work out, as they miraculously did in our courses, a splendid time can be guaranteed for all, to paraphrase John Lennon.