A Look at the Intersection of Scientific Rigor, Big Data, and Interdisciplinary Training

Alois Saria is a professor and head of the department of the experimental psychiatry unit at the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria. As the director of the European Union’s Human Brain Project’s Education Program and member of SfN’s Neuroscience Training Committee, Saria is actively involved in leading conversations and instituting new models to help neuroscience training and research cut across fields, incorporate new technologies and approaches, and usher in more discovery. In this interview, Saria shares insights from these experiences to highlight the importance of following scientific rigor best practices and fostering interdisciplinary training to advance neuroscience research.

Why is it critical for all scientists to understand and implement scientific rigor?

Every scientist has a responsibility to other scientists to publish accurate and reproducible data to advance the field. After all, we all read our colleagues’ publications and use their published data as a basis for developing our hypotheses. If we do not follow scientific rigor carefully, our colleagues may end up in a dead-end street — and waste public money — because we haven't been responsible enough.

What should trainees in particular keep in mind about scientific rigor?

Scientific rigor is important at all career stages. But it is especially critical for younger scientists to know what scientific rigor means and the potential consequences of not adhering to it. Young scientists are focused on publishing papers. They want to get into high-impact journals and build their bibliometric data to advance their careers. But if they do not carefully follow the rules and features of scientific rigor, they can quickly end up in troublesome situations. For example, a non-rigorous paper may get rejected, or, if it does get published, later on it may get retracted — which can ruin a career.

How are scientific rigor practices shaping some of the newer or evolving areas of neuroscience?

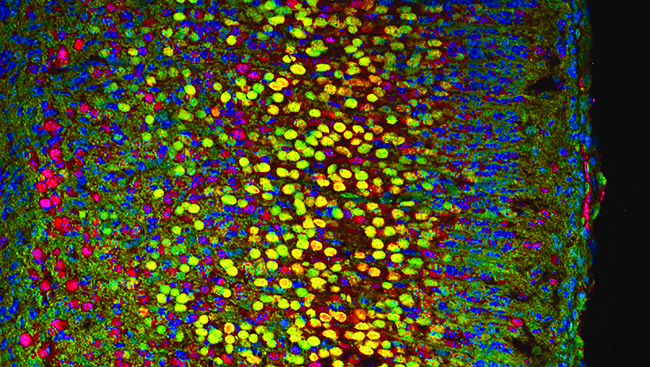

The Human Brain Project (HBP), an international, big data collaboration in which I am the director of the education program, is a clear example. HBP is funded by the European Commission and has 120 partners and hundreds of participating scientists. We are trying to develop infrastructures so that the scientific community can conduct experiments using big data approaches for simulating brain models.

One major question to solve is determining which data we can use. Data have to be correct. It can be very difficult — in some cases impossible — to select the valuable data from what we call “rubbish data” that did not follow the rules of scientific rigor. We also have to figure out how to standardize data published by different people all over the world who used varied techniques.

Another challenge is trust. You have to be absolutely sure that your partners produce solid, reproducible data resulting from applying scientific rigor and care. Currently, with so many expensive, new techniques, collaborations have become more important, and larger. Yet you cannot always pick the colleagues you trust based on prior personal interactions because you are now more or less dependent on who is available in the market. In these situations, you have to trust others without being able to rely on personal experience, meaning that scientific rigor becomes even more important.

These issues are also at the forefront of other big brain research initiatives, such as in the United States with the BRAIN Initiative, China, Australia, and Canada. So, even to compare, partner with, or look for symmetries among these efforts, it's of the utmost importance that we can trust the data.

Interdisciplinary training is another big focus of the HBP. What is the project’s approach, and what’s needed to better integrate the sciences on the bigger scale?

The HBP involves engineers, physicists, computer programmers, neurobiologists, biochemists, and physicians. This collaboration reflects the way brain research is becoming more interdisciplinary, especially as mathematical modeling, big data, and neuroinformatics are becoming more important to develop new brain simulation models.

When we ran the first HBP workshops and summer schools, the differences in computer scientists and neurobiologists’ technical language, way of thinking, and approaches to problem-solving and experimental design surprised me. There is clearly a need and opportunity to close the gaps and increase understanding among the different scientific fields at the university level as new initiatives like the HBP carry brain research forward.

And we are all still learning the best tools and methods for doing that. In Europe, most universities still follow their traditional education curricula, and at the moment, I am not aware of any European university curricula that bridges all the disciplines represented in the HBP. Neuroscience programs in the United States seem to be a little better in terms of incorporating computing and mathematics.

Overall, there has to be a paradigm shift and development of new university curricula that focus more on linking different disciplines. Efforts like HBP and organizations like SfN and others are well-positioned to foster discussions on the neuroscience field’s overall strategies for updating curricula, methods, and approaches to serve research in the best way possible.

What else can help trainees to broaden their skillsets?

Many trainees are very focused on their own work. However, it is important for them to expand their knowledge of other research areas by exploring other labs. This can help broaden their way of thinking and approaching problems.

In Europe, while mobility is not that well developed, the situation is improving. The European Union has helped by fostering different programs that increase student mobility.

Individually, advisers and trainers have a responsibility to convince their students to explore labs that complement their research. They can encourage trainees to use their own networks to find places for lab visits. It takes some effort, but it is worth it.

Speaker