What is the job of a journal reviewer? Whether you’re looking to become a reviewer, just starting out, or want a refresher, here are the four major areas of responsibility of all peer reviewers.

1. Assess the work for its rigor.

Is this high-quality research or not? Were all of the controls used in the experiment both positive and negative controls? Did the authors really measure what they say they measured, meaning was there sufficient fidelity in the technique to detect the magnitude differences they identify? Alternately, if the authors state something was undetectable, can they prove that they could measure something else as a positive control? Was the statistical analysis done properly? Do they have an appropriate sample size to give them sufficient power to detect the effects that they say that they are detecting or not detecting? Sometimes people underestimate the power that you need to get a negative effect. It's just as important as the power that you need to get a positive effect.

In addition, are the statements of fact in the manuscript actually supported by data? It's not uncommon for authors to overstate their findings, or to connect dots that are not present in their data set. Reviewers call it going beyond your data and making conclusions not supported by the research.

2. Identify missing information.

This is also related to reproducibility in science. You can't properly assess the work if you don't know exactly what was done. For instance, what was the species studied, the strain, the age of the animals, the sex of the animals, and the housing conditions? In addition, what were the timelines, the treatments, and the measurements? What were the doses? What antibodies did they use? The authors aren’t leaving out this information on purpose, but rather it's so obvious to them that they may forget to mention important details.

It’s your role as a reviewer to make sure that there has been sufficient scholarship in the presentation. Is there an appropriate referencing of the literature? Have they cited the relevant prior work? Have they cited the classic work that led them to where they are today? Have they cited any work that contradicts their findings? That's equally important.

3. Detect internal consistencies.

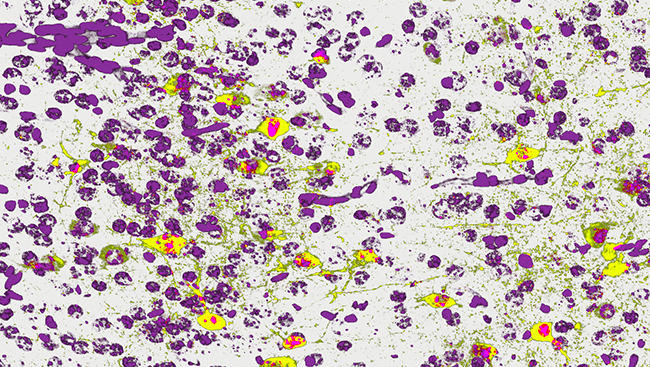

Make sure that the figures are cited appropriately, that the numbers in text and the figures match, that all of the information in the figures is cited, and that the scale bars, axis, and controls are consistent across figures, and that the controls aren't repeated between figures. Confirm that the numbers don't seem so closely aligned that they look like they might be identical. Check across figures that are measuring similar endpoints to see that the y-axis is consistent across them.

Also make sure that images are not repeated, particularly when it comes to a photo micrograph and cellular images. Accidents can happen. Sometimes people are dealing with large amounts of information, and they might inadvertently have repeated a figure. You're there to help identify that for them and for the editor.

4. Evaluate the effectiveness of the presentation.

Take a 30,000 foot view and ask, "Am I really getting the story that they're trying to tell me here? Are the figures effective in what they are portraying? Should some of the data be in a table? Should that data that's in a table actually be in a figure? Would I like a summary diagram to pull all this information together for me?” The style of the writing is important as well. The tenses used should be consistent throughout: Use past tense for current results because it’s what was observed and current tense for past results as they are established facts.

Adapted from SfN’s webcast, Tricks of the Trade: How to Peer Review a Manuscript, which is available for all members to watch on-demand.