Advice for Navigating Academia as a Black Woman

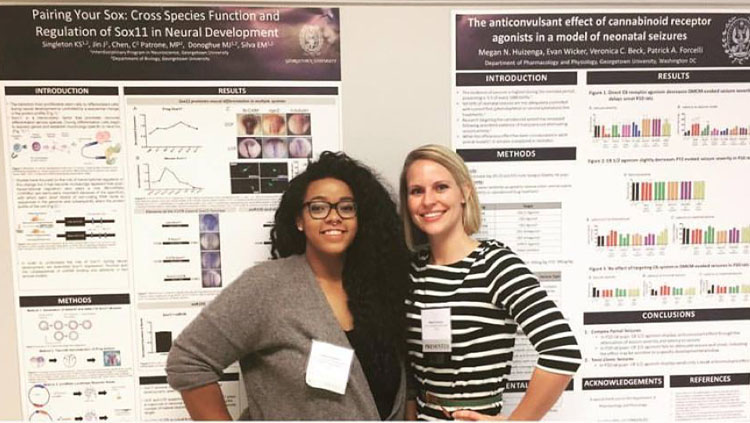

Kaela S. Singleton is an NINDS D-SPAN scholar, adjunct professor at Agnes Scott College, and a mentor to her students at Agnes Scott College and Emory University. In this interview, Kaela recounts her experience with imposter syndrome and how to navigate implicit bias in academia. She also discusses successful mentor relationships and her hopes for the future of diversity in academia.

Walk us through your career path.

I've been interested in neuroscience since seventh grade when I got to dissect a sheep's brain through a science outreach program. That was the only activity in school I thought was really cool and I could imagine doing for the rest of my life. I ended up choosing Agnes Scott College because it had a well-defined neuroscience major.

I started research in undergrad and worked in several labs that focused on neurodevelopmental disorders. In graduate school, I researched the molecules that regulate neural development across species and how they differ in function despite being highly conserved across species. My postdoctoral work is focused on neurodevelopmental disorders, using my foundational molecular neuroscience research skills and developmental approaches to investigate how copper and environmental toxins affect fetal development. Despite being a grad student, I didn't think an academic career in neuroscience was a true option for me until I was in my fourth year of graduate school. Up until then I kept going because I enjoyed it and thought it was interesting. I eventually realized there was a reason I was good at it, and that I could be a professor or have my own lab if I wanted.

What are some challenges you have faced and how did you navigate them?

The most profound challenge I've faced is being a Black woman who exists in predominantly white spaces, where I am expected to shrink myself to fit this mold that wasn't made for me.

There have been other discouragements. Every scientist experiences frustrations, but I've also dealt with active discouragement from mentors in graduate school. They told me not to apply to fellowships because I wasn't competent or qualified enough. They said I should leave academia because I wasn't cut out to be a professor and lacked professionalism. It was hard to hear from someone in authority that I wasn't good at what I'd pursued for quite some time.

It was a soul-crushing moment for me, and I just believed them. I thought, "Why did I think I could do this?" Through other people in my community, I realized they were wrong and had no idea what they were talking about. My peers became my mentors, validating my emotions and experiences, and they helped me polish my ideas and see their value.

How do you define implicit bias?

Implicit bias is a knee-jerk response to the way someone behaves, and it's at the root of microaggressions.

Saying to Black people, "You are really articulate or professional," comes from a place of implicit bias in how you perceive Black people. You think you're giving someone a compliment because of preconceived internal notions you have about a broad group, but in actuality, you're insulting them by revealing you think all Black people aren't professional or don't speak well.

How have you dealt with it?

It took me a long time to realize I was being affected by implicit bias and microaggressions. I thought graduate school was this hard for everybody. I thought everybody was told they weren't competitive enough for grants, talked down to, or assumed to have traumatic stories from their past to use in a personal statement.

One of the best ways to handle microaggressions is to realize not everything deserves a response in that moment. If you can't bring yourself to say, "That was pretty racist," it's okay to take time and sit with it, and either advocate for yourself later or ask a friend, peer, or mentor to advocate for you. In graduate school, I had a great friend who stood up for me several times when microaggressions would come up in conversations. I think sometimes her voice was heard more because she's a white woman. When I did speak up for myself, the attitude was, "Well you're just being sensitive and making everything about race."

What advice do you have for confronting imposter syndrome?

I still deal with imposter syndrome to this day.

The negative comments from a faculty member whose lab I left stunted my confidence in my ability to do science from an early stage. Her comments like, "You're only winning these awards and being nominated because you're Black," still ring in my head.

Impostor syndrome can be complicated. You not only feel like a fraud, but you also feel like you don't belong in this space, and those can be two different feelings. One is, "Someone's going to find out I'm an idiot." The other is, "This space actually isn't made for me at all, so of course someone's going to see that I don't fit."

The best advice I give people when dealing with impostor syndrome I got from my Nana when I was little: Take up as much physical space as you deem necessary to be unapologetically yourself. Ask not only for what you want, but what you need, and don't worry about someone being upset with you for it. Stand firm and allow your voice to be heard.

Who are your role models?

Michelle Jones-London, Marguerite Matthews, and Bianca Jones Marlin because they are Black women who uplift other Black women. Their magic and power come from this place that is intentionally permissive, where they actively work to make spaces better for future trainees, ask you to be the best version of yourself, and use their voices, platforms, and decorum to increase neuroscience diversity. Michelle Jones-London was the first Black person with a PhD I ever met, in 2012 at the SfN annual meeting, and she inspired me to go to graduate school.

What makes a good mentor?

Pick a mentor who inspires and motivates you to think critically about your science and your career. Find a mentor that is invested in your growth as a person and scientist from the beginning.

As a mentor, I try to make sure I am authentically myself in all spaces, and not shrinking or changing myself when I'm in different rooms. I introduce myself to my students as Dr. Kaela S. Singleton, a Black Queer woman and developmental neuroscientist. I try to make sure I'm accessible to students, even on social media, and that we can engage in conversations about science, life, whatever really.

I think speaking about your experiences of racism and sexism can also be powerful and motivating for students. It lets them know they're not alone, and that other people have similar experiences and have come out on top. I feel it's my obligation and responsibility to talk about those issues, and to make my academic spaces safer, more inclusive, and understanding.

What changes would you like to see in academia?

I want to see people of color, predominantly Black women, compensated for the emotional labor it takes to exist as diverse people in academia. Serving on diversity, equity, and inclusion committees is great, but oftentimes it doesn't lead to immediate change, and their voices are not heard. On top of that, they have to go back to their offices and help the diverse student population navigate a predominantly white space. People don't realize how taxing that is or how much energy that takes.

I was the only Black graduate student in my department, so other Black students came to talk to me about problems with faculty members. I don't mind, but it is taxing.

I want an increase in diverse faculty, but I also want to make sure that those diverse faculty aren't put in negative or traumatic environments where they're ultimately going to leave because they don't have resources they need. I want inclusivity and equity. But I also want diversity, equity, and inclusion to evolve into representation and accountability, where faculty members from all backgrounds are held accountable for their actions and the environments they create.

What are your hopes for the future?

I think science has to remove itself from this idea that it's apolitical. Addressing and acknowledging the racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia that exist in academia is really an integral part of becoming a better scientist. We need more tenured faculty to demand change and put it all on the line to support their Black and underrepresented trainees.

I want underrepresented researchers to know their dreams are possible. My peers and I are actively working to make sure the academic space is better for them. We're using our platforms and our voices to speak out about the injustices we see at all levels.

Speaker